How news can confuse: What's behind some recent headlines

Everyone eats. So news outlets know that the latest food study is likely to grab eyeballs. But sometimes the media doesn’t get it quite right. Sometimes they neglect to mention that the headline shocker comes from a study in test tubes or from a study that can’t prove cause and effect. Sometimes the study itself is at fault. Often, the media simply repeats a press release’s mistakes. Here are a few “Oops!” stories that confused many.

“This new study looked back over five decades of studies and found eating chocolate more than once a week was associated with an 8% decreased risk of coronary artery disease,” reported CNN.com in July.1

“Our study suggests that chocolate helps keep the heart’s blood vessels healthy,” study author Chayakrit Krittanawong of Baylor College of Medicine told CNN.

Not quite. The new study combined the results of six earlier studies. But one of them was only published as an abstract (a brief summary). After Krittanawong’s team re-examined the data without that study, poof! The link between chocolate and heart disease evaporated. Oops.

Dark chocolate has “a much lower sugar content and fewer calories than milk or white chocolate, because those are mixed with powdered or condensed milk,” noted CNN.

Really? An ounce of Dove Dark Chocolate has only 10 fewer calories and 1 gram less added sugar than an ounce of Dove Milk Chocolate.

Bottom Line: Studies like these—which ask people what they eat, then follow them for years—can’t prove that chocolate protects the heart. A clearer answer should come from the COSMOS trial. It’s testing whether 600 milligrams a day of a cocoa flavanol supplement can cut the risk of heart disease and stroke. That same amount of flavanols from dark chocolate would come with roughly a 600-calorie price tag.

1Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 2020. doi:10.1177/2047487320936787.

“Three or more servings per day of what researchers call ‘ultra-processed food’—mass-manufactured foods containing oils, sugars, fats, starch and little nutrients—may lead to changes in chromosomes linked to aging,” reported foxnews.com in September.

A recent study “found that having multiple daily servings of junk food, like cookies, chips, fast-food burgers or other processed meals, doubles the chance that certain strands of DNA, called telomeres, would be shorter than those who ate healthier,” said Fox, adding that “shorter telomeres are a marker of accelerated biological aging.”

This study aside, it’s smart to cut back on ultra-processed foods. For example, in a carefully controlled trial, people ate an extra 500 calories per day and gained two pounds after eating largely ultra-processed foods for just two weeks. They lost two pounds after eating unprocessed foods for two weeks.1

But the study that Fox reported on didn’t show that eating ultra-processed foods accelerates aging.

The researchers simply asked people what they typically ate, then measured the length of their telomeres.2

Did the ultra-processed foods in their diets cause the shorter telomeres? Or does something else about people who eat ultra-processed foods explain the link? This type of study can’t say.

As the authors noted, “although we adjusted for several potential confounders, other potential confounders may exist.” Oops.

Bottom Line: The study didn’t randomly assign people to eat either unprocessed or ultra-processed foods, so it can’t prove that ultra-processed foods shorten telomeres. But those foods can pad your waistline. That’s reason enough to build your diet around unprocessed fruits, vegetables, beans, and whole grains.

1Cell Metab. 30: 67, 2019.

2Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 111: 1259, 2020.

"Here’s one reason not to feel guilty about your next pizza binge,” reported fastcompany.com in July.

“A new study of people who overindulged in the popular food found that their bodies maintained healthy blood chemistry, with no immediate poor health effects.”

“Participants were asked to eat pizza until ‘comfortably full,’ and then, at a later date, until they ‘could not eat another bite,’” said the website. They ate about 1,600 calories the first time and 3,100 the second.1

After they overate, “blood sugar levels stayed steady” compared to after they ate the smaller portion, “while insulin levels doubled (to control the blood sugar levels).” And “blood lipids (triglycerides and fatty acids) were only slightly higher.”

Slightly? In fact, both insulin and triglycerides rose by about 50 percent more after the larger meal than after the smaller one. (Triglycerides rose because people ate a lot of fat.)

“The overeaters were lethargic for a prolonged period of over four hours,” noted Fast Company. Guess that’s not one of the “surprisingly good things” about a pizza binge.

“This study shows that if an otherwise healthy person overindulges occasionally, for example eating a large buffet meal or Christmas lunch, then there are no immediate negative consequences in terms of losing metabolic control,” the senior author, James Betts of the University of Bath in England, told Fast Company.

But who cares about “immediate” consequences?

What’s more, the 14 pizza eaters weren’t typical. The men were 22 to 37 and at or just slightly above normal weight.

In contrast, 72 percent of adults have overweight or obesity, 48 percent have prediabetes or diabetes, 46 percent have high blood pressure, and 29 percent have high LDL (“bad”) cholesterol.

That said, no one would expect those problems to appear after just one meal. So why make such a fuss about the results?

While the study “did not receive any direct funding,” the paper disclosed that four of the researchers had ties to the food industry. Fast Company—and other news outlets—left that out. Oops.

Bottom Line: With a typical restaurant entrée (sans appetizer, drink, or dessert) hovering around 1,000 calories, the last thing we need is license to “binge.”

1Brit. J. Nutr. 124: 407, 2020.

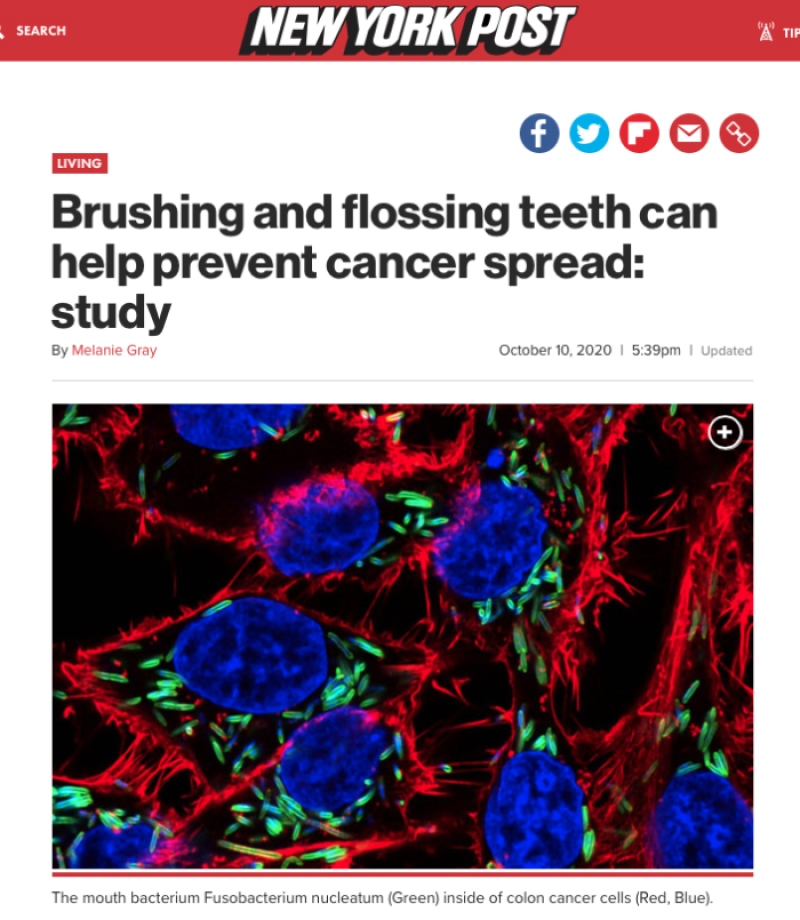

"Brush, floss, gargle—advice coming now from cancer researchers, not just your mom and dentist,” reported the New York Post in October.

“Scientists are stressing good oral hygiene after they discovered a common mouth germ can push cancer to other parts of the body.”

Yikes.

“And they see their finding as significant because the spread of the cancerous cells—or metastasis—is what causes 90 percent of cancer deaths.”

Needless to say, any study that finds a way to stop cancer cells from metastasizing would be a blockbuster. But this fascinating study didn’t exactly go there.

It focused on Fusobacterium nucleatum, one of many bacteria that live in our mouths. According to the Post, “colon cancer cells invaded by the germ became inflamed by two proteins called cytokines—and the inflammation in turn caused the cells to travel.”

Not quite. It was actually the cytokine-rich goo surrounding the infected cancer cells that led another set of uninfected cancer cells to travel.1

But that’s just a detail. The glaring error: The Post neglected to mention that the study took place in test tubes—actually, lab dishes—not in people. Those cells traveled from one end of a lab dish to the other, not “to other parts of the body.”

And what happens in test tubes may not happen inside us. Oops.

What’s more, even if this bacteria matters, it’s a leap to assume that brushing or flossing your teeth might be enough to keep it—and cancer—from spreading.

Bottom Line: Brush and floss frequently to prevent gum disease. But it’s way too soon to know if taking care of your teeth and gums can keep cancer from spreading.

1Sci. Signal. 2020. doi:10.1126/scisignal.aba9157.

The study sounds impressive. Researchers “looked at data collected on 112,922 people as part of the Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology (PURE) epidemiological study,” reported Newsweek in May.

“Participants were aged between 35 and 70-years-old from 21 countries on five continents.”

Among the results: After asking people what they typically ate and waiting years, “a higher intake of whole fat, but not low fat, dairy was linked with a lower incidence of high blood pressure and diabetes,” explained Newsweek.

Well, not exactly. Those links were only statistically significant when the researchers lumped all dairy foods together, not when they looked at either whole-fat or low-fat by itself.1

Also, as the researchers noted, “our study was underpowered to detect an association” in the low-fat-dairy eaters “owing to a low number of participants in this particular group.” Oops.

What’s more, only four of the 21 countries (Canada, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, and the United Arab Emirates) were high-income, and half of the participants were from regions of Asia or Africa where dairy is not frequently consumed. As the study notes, “dairy intake might be a proxy for poverty or access to healthcare.”

So it’s hard to know if the results apply to our dairy-laden diets.

To its credit, Newsweek provided some balance.

“Choosing low and reduced fat dairy is one easy way to cut down on saturated fat intake to help lower cholesterol levels,” a dietitian for the British Heart Foundation told the magazine.

“The American Heart Association continues to recommend a heart healthy dietary pattern”—like a DASH or Mediterranean diet—noted one of the group’s past presidents.

Too bad Newsweek failed to mention that the dairy industry helped fund the study.

Bottom Line: Clinical trials are testing high-fat and low-fat dairy on blood sugar and insulin. Until results are in, stick to low-fat dairy to keep a lid on your LDL (“bad”) cholesterol...and to save calories.

1BMJ Open Diabetes Res. Care 2020. doi:10.1136/bmjdrc-2019-000826.

"Glaucoma strikes many people as they age, but what if a simple dietary change could lower your risk?” asked a HealthDay article on USNews.com in July.

“The researchers analyzed data from 185,000 female nurses and male health professionals, aged 40 to 75,” said the article.

“Maintaining a long-term diet low in carbohydrates and high in fat and protein from vegetables was associated with a 20% lower risk of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) with early paracentral visual loss, according to the study published online recently in the journal Eye.”

Umm. Did the reporter read the study? Here’s its main conclusion: “Low-carbohydrate diets were not associated with risk of POAG.”1

Nor did the researchers find a link with low-carb diets when they looked separately at glaucomas that damage peripheral vision versus glaucomas that cause damage near the center of the field of vision.

Only when the investigators broke down the types of low-carb diets—into those heavy on animal versus vegetable foods—did they find the reported link with central vision alone...sort of.

Even that link wasn’t statistically significant. (The study calls it a “suggestive” association.) Oops. So what led to the eye-grabbing headline?

“Low-carbohydrate diet may be associated with lower risk of blinding eye disease,” announced a press release from the Mount Sinai Health System in New York, where one study author is deputy chair for ophthalmology research.

Could that misleading headline have caught HealthDay’s eye?

Bottom Line: Cut back on refined carbs (added sugars and white flour) to make room for more vegetables, fruit, beans, whole grains, and nuts. Just don’t expect a low-carb diet to lower your risk of glaucoma. The evidence is far too scanty.

“Poor sperm quality has been linked to using electronic media at night, according to new research released by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine,” reportedfoxnews.com in September.

“New research” is an understatement. As Fox later notes, “the preliminary results” were “published as an abstract”—that is, a brief summary—in the journal Sleep.1

“‘Smartphone and tablet use in the evening and after bedtime was correlated with decline in sperm quality,’ said principal investigator Amit Green, Ph.D., in a press release,” wrote Fox.

“Furthermore, smartphone use in the evening, tablet use after bedtime, and television use in the evening were all correlated with the decline of sperm concentration.”

So...those attention-grabbing headlines were based on a press release about an abstract?

Men who used their phones and tablets more in the evening and after bedtime were more likely to have lower sperm concentration and motility.

What else about heavy-phone-and-tablet users did the study take into account? Could it be less sleep, not light-emitting screens, that explains their lower sperm quality? The abstract didn’t say.

As it turns out, the full study had been published six months before the Fox News item. And less sleep was indeed linked to low sperm quality.2

But even the full study couldn’t tease out whether sleep or phones and tablets—or neither—causes a drop in sperm quality. Oops.

Bottom Line: It’s far too early to say whether light-emitting screens lower sperm quality.

1Sleep 2020. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsaa056.028.

2Chronobiol. Int. 37: 414, 2020.

"If you’re an acne sufferer who has long thought chocolate, sweets, dairy and other fatty foods made your acne worse—even though your doctor said it was all in your head, not your face—you’ve been vindicated,” reportedCNN.com in June.

The vindication: a new study of nearly 25,000 French adults.1 “Compared with people who never had acne, those with current acne consumed significantly more milk, milk chocolate, snacks and fast foods and fatty and sugary products. They also ate significantly less meat, fish, vegetables, fruits and dark chocolate (which has less milk),” explained CNN.

“After adjusting for sex (including pregnancy and menopause status), age, smoking, physical activity, educational level, depression, weight, diabetes and other diseases,” said CNN, “consumption of milk, sugary beverages, including sports drinks, and fatty and sugary foods were found to be independently associated with current acne.”

Wait, what?

So the links with most items in the first list of foods (like milk chocolate, dark chocolate, and snacks and fast foods) disappeared after adjusting for age, smoking, weight, and other potential confounders? Then why even mention those foods...and in the headline, no less? Oops.

The study’s other shortcomings: a third of those with acne had diagnosed it themselves; the researchers didn’t define “fatty and sugary foods”; and the study was done in adults, so the results may not apply to teens, who are most likely to have acne. Sheesh.

Bottom Line: To find out if a food causes acne, researchers can randomly assign people to diets with or without it. This kind of study, on the other hand, can only suggest which foods to test.

1JAMA Dermatol. 156: 854, 2020.

Continue reading this article with a NutritionAction subscription

Already a subscriber? Log in