What kind of study?

Here’s a quick primer on the two types of studies on diet and health you’re likely to hear about, and a few of their pros and cons.

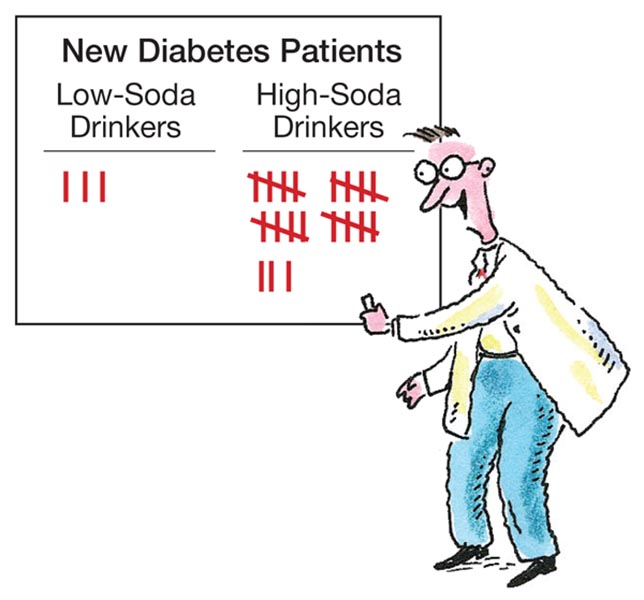

Observational studies

Most are “prospective cohort” studies that ask thousands of people what they typically eat, then wait five or 10 years to see who gets heart disease, diabetes, cancer, etc. The best studies filter out the impact of smoking, exercise, and other potential “confounders”—that is, something else about the participants or what they do that accounts for the results.

Pro: You can see a decade’s-long impact on health.

Con: You can’t tell if unknown confounders explain the results.

Randomized clinical trials

Researchers randomly assign people to eat one of two (or more) diets. The best studies provide all the food. After a few months, the scientists see if the diets made a difference in a risk factor (like blood pressure). If trials want to look at diseases like diabetes, cancer, or heart disease, they typically have to enroll thousands, wait for years, and rely on participants to choose their own food.

Pro: If the study finds a difference in a disease or risk factor, you can be sure the diet caused it.

Con: If a diet has no effect, it’s possible that people didn’t stick to it, or that the trial was too short or too small.

Illustrations: Loel Barr. Photo: apinan/stock.adobe.com.

Continue reading this article with a NutritionAction subscription

Already a subscriber? Log in